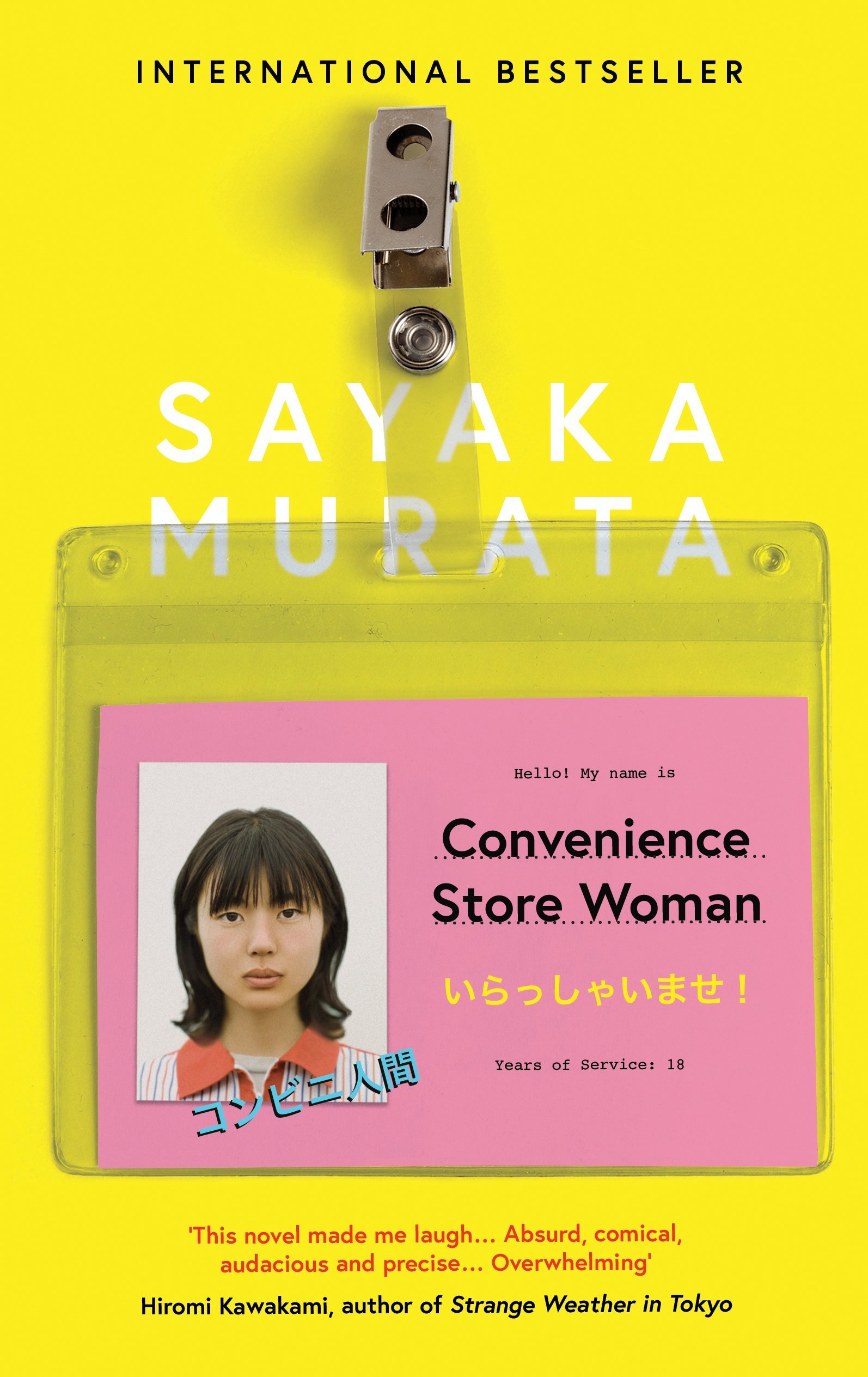

Exploring the Neurodiverse Voice: A Review of Convenience Store Woman (2016)

By Alecsander S. Zapata

There’s a scene from the 2000 film American Psycho (one of my all-time favorites) in which protagonist Patrick Bateman (played by Christian Bale) tells his fiancé that he doesn’t quit the job that he hates because he “wants to fit in.” For those unfamiliar with Mary Harron’s film, or Bret Easton Ellis’ novel, for that matter, Patrick Bateman is, as the title suggests, psychopathic to the extreme. He is almost entirely without emotions or empathy and is driven further and further into degeneracy by his unquenchable bloodlust. In a similar vein, it is the sentiment of wanting to fit in that brings us to Convenience Store Woman (2016). This absolute gem of a novel, authored by Sayaka Murata, is, for the sake of comparison, a more up-to-date entry into the canon of works that delve into the psychology of extremely neurodiverse characters in the way that American Psycho does. But whereas Patrick Bateman’s character is more defined by his homicidal urges, protagonist Keiko Furukura is retooled, recontextualized, and almost entirely defined by her desire to fit in and pass as “normal.”

Keiko is a 38-year-old convenience store worker in Japan who considers herself “reborn” since she first began working there eighteen years prior. Over the years she has become more and more attached to this identity because the structure, routine, and expectations of convenience store work coincide nicely with her strengths and are not affected by her limitations. In fact, Keiko spends a good portion of the narration detailing the “forcibly normalized atmosphere” that is a Japanese convenience store and the techniques that she employs to not be outed as the kind of “foreign matter [that] is immediately eliminated.” This includes copying the vocal patterns and inflections of her coworkers depending on the situation at hand, finding clothes that are age-and-status appropriate for her, and, generally, following the store’s worker’s manual to a tee. As there is no manual for behavior outside of the store, she cherishes the structure provided by her work.

For a character as non-conformist as Keiko, in a literary sense as well as a societal one, the novel requires a strong and expansive framework of narrative rules, something that Murata does not shy away from at all. And while the mystery regarding whether or not she is capable of an emotional experience is one of the philosophical questions being posed to the reader, we are first given the baseline assertion, from Keiko herself, no less, that she does not, in fact, feel. That is the lens through which we are first introduced to our protagonist.

How, then, does such a person think and observe the world around them? What impulses them from Point A to Point B? How would such a person use up their time or approach conflicts? The fact that Keiko is so far removed from the assumed audience naturally leads the reader to these kinds of questions. For the most part, Murata handles them extremely well, building Keiko’s psychology from the ground up and covering up almost any hole that the narrative might produce as a result of such a uniquely constructed narrator.

Keiko’s voice is not only fascinating but also genuinely fun to read, imbued with both intelligence and levity. Keiko ponders the world of the convenience store, the world that she understands and the sounds of which invigorate the very cells of her body, just as much as she ponders the normal world that she does not understand or connect to at all. Her questioning of behavioral standards (which are certainly informed by the contemporary Japanese culture of which she is part, while also expanding far past any national or cultural border) can sometimes seem shocking, but often they are hilarious and thought-provoking. Likewise, her pragmatic and logical worldview is often contrasted with the emotional nature of other people and the expectations that are placed on her.

Her group of friends, for instance, become increasingly frustrated with her for not pursuing a lifestyle that is in line with their own, and the precision of her clothing and general appearance cannot make up for the fact that she is a thirty-eight-year-old convenience store worker with no further ambitions. And yet, their frustration does nothing to make her feel as if she should have ambition—she knows that she is supposed to be normal, but she doesn’t know why. It’s a wonderful stroke of ingenuity to craft a novel in which the protagonist is embroiled in a kind of conflict that they are incapable of understanding.

The novel has stakes, of course, and it is perhaps Keiko’s inability to feel the external pressure being placed on her that makes the reader all the more worried for her, which is another masterstroke on Murata’s part. Her conflict with normal society is resolved, in the kind of oddball way that the work thrives off of, but the novel makes a point of not prioritizing the plot over the exploration of Keiko’s psychology. Learning about “who Keiko is” never becomes less important than learning about “where she is going” or “where she will end up.” Like Keiko herself, Convenience Store Woman is not concerned with the expectations her audience may have of what a novel should be. It has its own goals and is fulfilled on its own terms. In that way, the novel becomes greatly powerful as a treatise on how we interact with the neurodiverse experience.

Alecsander Zapata has devoted his life to the storytelling craft. He follows two core tenets which frame his philosophy on literature: one, that it is the question minus the answer, and two, that it can be found anywhere. He is soon to graduate from the University of San Francisco with degrees in English and Spanish.